Toni Morrison 1931-2019

Toni Morrison, a giant of world literature, was Albert Schweitzer Chair in the Humanities at UAlbany and a member of our office family during the very beginnings of our organization in the mid-1980s.

Toni Morrison speaks at the University at Albany in 1984, with Writers Institute founder William Kennedy in the background at right. (Fred McKinney / Albany Times Union file photo)

Toni Morrison exhibit

On February 13, 2026. the New York State Writers Institute installed an exhibit at the University at Albany's Science Library featuring Morrison's desk and chair — underscoring her indelible impact on future generations of writers. The installation demonstrates that the University was not simply a backdrop to greatness, but a place where greatness was unleashed. Read more

"If you find a book you really want to read but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it."

-- Toni Morrison, 1981

The first African-American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, Toni Morrison wrote 11 novels as well as children’s books and essay collections. Among them were celebrated works like Song of Solomon, which received the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977, and Beloved, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1988.

Toni Morrison was a frequent collaborator in the early days of the New York State Writers Institute at the University at Albany. Following the Institute's inaugural event with Saul Bellow in 1984, Morrison became the second speaker in our history when a packed audience greeted her in the Campus Center Ballroom on September 13, 1984.

In January 1985, she joined the University as the Albert Schweitzer Chair in Humanities, marking the first time the NYS Board of Regents has awarded the University the prestigious position. In that capacity, she brought Ralph Ellison, acclaimed author of The Invisible Man, to the University, along with performers Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis and other luminaries of the African-American experience.

“Toni Morrison was the rarest of rare birds,” said William Kennedy, Writers Institute founder and executive director. At that time, the Schweitzer Chair offices and the Writers Institute shared office space at the University from 1984 to 1989.

“She was a singular voice in American literary history,” Kennedy said. “She had a deep commitment of her whole being to create her powerful narratives. Her novels had such a lyrical quality and a powerful eloquence. That combination was profound in her work. She probed the depths of racism and the African-American experience in her fiction and her achievement is absolutely without precedent.”

Kennedy and the Writers Institute raised money and offered support for Morrison that allowed her to finish writing her first play, “Dreaming Emmett,” which premiered at Capital Repertory Theatre in Albany in January 1986, marking the first official observance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. In a New York Times story published December 29, 1985, Morrison talked about her first venture as a dramatist. "I keep asking Bill Kennedy to find one American who wrote novels first and then successful plays. Just one. And neither he nor I could come up with any one American... But I feel I have a strong point. I write good dialogue. It's theatrical. It moves. It just doesn't hang there."

“We had a lot of conversations about play writing,” Kennedy recalled. “We were both very interested in writing for the movies at that time, as well.”

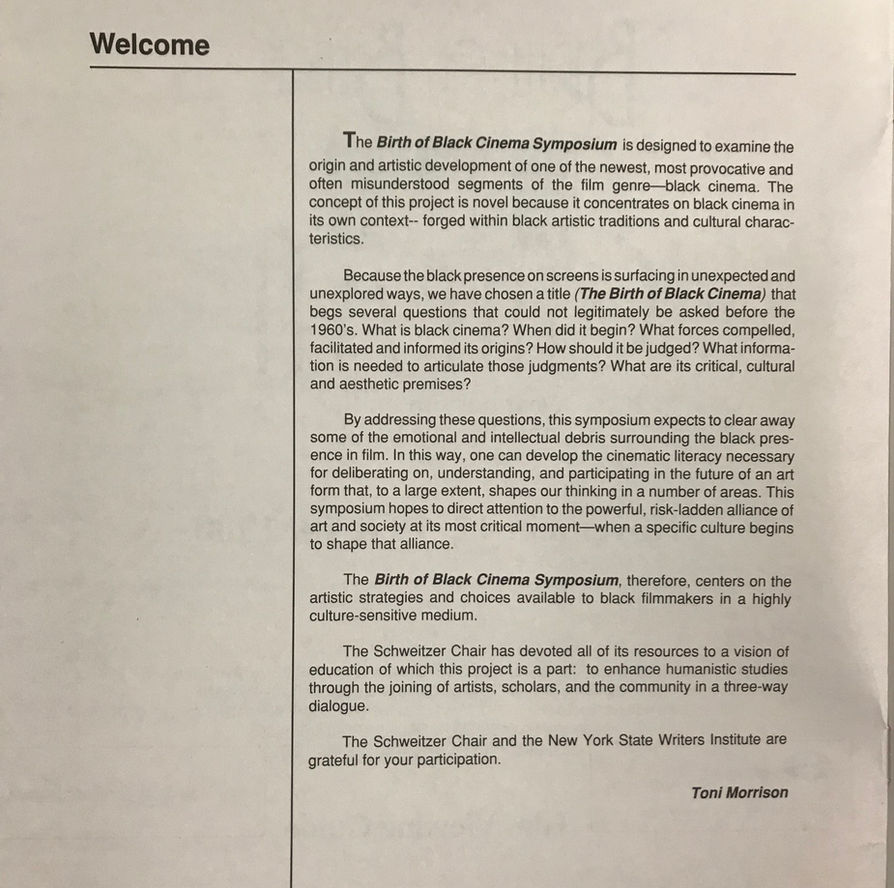

Morrison also produced "The Birth of Black Cinema" three-day symposium in 1988 featuring Spike Lee, Toni Cade Bambara, St. Clair Bourne, Haile Gerima, James Snead and Hortense Spillers.

"Everything I've ever done, in the writing world, has been to expand articulation, rather than to close it, to open doors, sometimes, not even closing the book -- leaving the endings open for reinterpretation, revisitation, a little ambiguity."

-- Toni Morrison, 1998

Paul Grondahl

Director, NYS Writers Institute

It is with great sadness that I write. Most or all of you have already heard the news that Karen Hitchcock died last night after a long, valiant battle with cancer. She was 76.

She was a friend to all of us and a remarkable person who enriched our lives, the Writers Institute and the University at Albany in immeasurable ways. We mourn her passing and remember so many good times with her.

In my head, I keep hearing her husky, full-throated laugh. She was a force of goodness and she certainly left her mark on our Friends of Writing advocacy group and this fine literary organization that we all love and support.

I spoke with Karen a few times in the past few months and she was very thankful for all of our calls and emails and cards. That meant a lot to her.

From the archives

A selection of photographs and news clippings from the NYS Writers Institute

Toni Morrison left her mark on Albany

While on faculty at State University at Albany in the mid-1980s, Toni Morrison taught writing, nurtured novelists, gave public readings, premiered a play, organized a film and staged reading series — all the while injecting a viewpoint that was strongly African-American and feminist.

Still, despite her reputation as celebrated novelist, esteemed critic and literary heavyweight, there was a playful and flamboyant side to Morrison that those who worked with her in Albany recall.

Here are some of those favorite Toni Morrison moments...

Writers Institute founder William Kennedy and Toni Morrison at the University at Albany in 1984. (Albany Times Union file photo)

SUZANNE LANCE, special projects officer for Toni Morrison at UAlbany beginning in 1984

"Toni Morrison was an intense presence and a powerful champion for African-American literature who also nurtured young writers during the five years in the mid-1980s that she spent at the University at Albany," said Lance.

Morrison had an office in a cramped suite on the third floor of the Humanities Building. Morrison did some writing and editing in the UAlbany office, where her secretary, Ronnie Saunders, re-typed Morrison’s freshly edited manuscript for Beloved.

Lance remembered receiving a call at their UAlbany office from a reporter with the news that Beloved had just won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

“Toni didn’t happen to be in the office that day, but we were thrilled for her,” Lance recalled. The staff and other University faculty and staff threw Morrison a congratulatory party with champagne and fresh strawberries in the University Art Museum.

“I remember Toni Morrison as really intense, very demanding and even a little intimidating,” recalled Lance, “She was brilliant and an absolute perfectionist.”

Morrison was not effusive with praise, but Lance recalled a wonderful compliment the great writer gave her. After proofreading the thick brochure that Lance had edited for “The Birth of Black Cinema,” a three-day symposium on campus in 1988, Morrison met with Lance. She reminded her assistant that she had worked for nearly 20 year as an editor at Random House and she had yet to find a published book that had fewer than three errors.

“Congratulations,” Morrison told Lance after carefully proofreading the brochure. “I only found two errors in your work.”

Lance felt like she had won a major literary award.

“I was impressed with the utmost seriousness that Toni Morrison brought to her position,” Lance said. “She could have taken the money and just phoned it in. But she expanded the programming, created new events and worked closely with young writers. She put in tremendous effort.”

Lance also recalled that Morrison had a wide network of amazing friends, whose numbers Lance kept in a Rolodex. “I remember I had Oprah Winfrey’s number,” Lance said. “It was a Who’s Who of phone numbers.”

“Nobody did more at that time in bringing black writers to campus and to the Albany community at that time,” Lance said. “That was part of her legacy.”

The Writers Institute kept some of Morrison’s office furniture, including a 1980s-vintage striped wing chair that she used at her desk at UAlbany. Director Paul Grondahl invites visiting writers to sit in Toni Morrison’s chair when he interviews them for the Writers Institute podcast.

“You should see their faces light up when I tell them they’re sitting in Toni Morrison’s chair,” Grondahl said. “Some of them close their eyes and imagine they are absorbing some of her spirit and writing magic.”

He added, “They always ask me to take a cellphone shot of them sitting in that chair. It seems to hold a special power for them.”

Below are excerpts from a 1993 Times Union story by Paul Grondahl upon the announcement of Toni Morrison's Nobel Prize

WILLIAM KENNEDY, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist who shared an office with Morrison

"She loves ice cream, so when she came out to our house, she brought us an ice-cream maker. She was a very generous person like that and full of great, good humor."

Kennedy called Morrison "a fiction writer of the first rank" and her award is a "singular event" given the fact that she is the first black woman to receive the prize. "As a friend of long standing, I delight in her recognition," he adds.

"But apart from that, this is a splendid moment for American literature."

Kennedy remembers a party for Morrison at his Dove Street town house, attending her birthday party in New York City and other parties. "I just remember laughing a lot with Toni," he says.

"She's a very vital person who celebrates life."

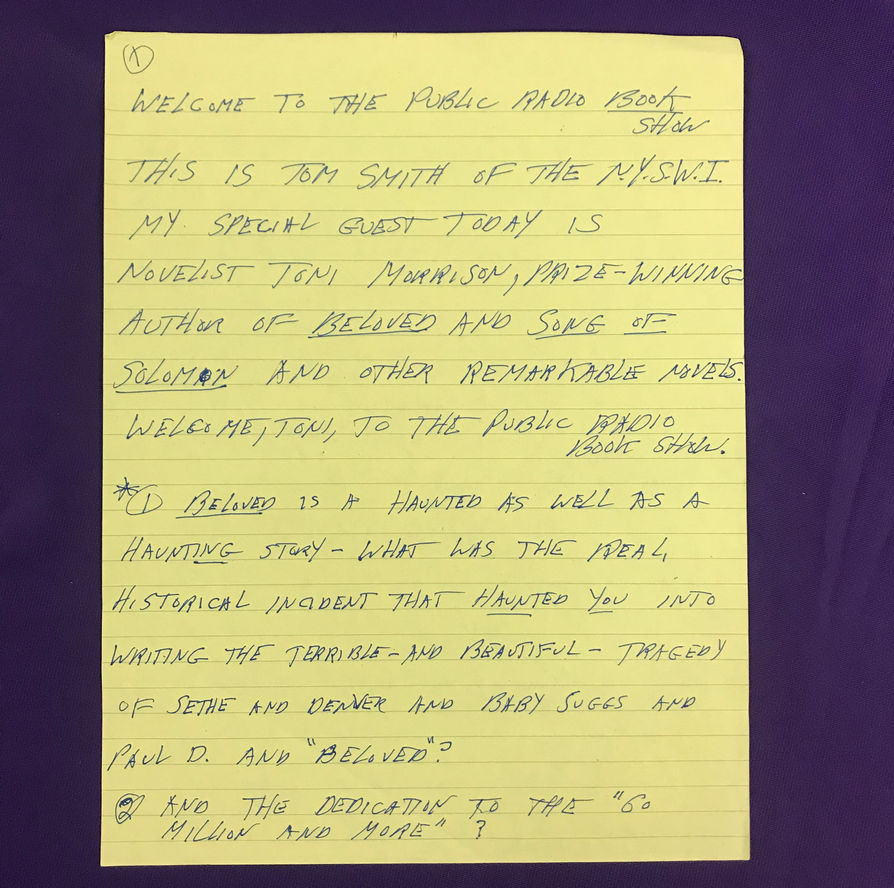

TOM SMITH, English professor, Writers Institute director, host of "The Book Show" on NPR

"She had a fantastic presence here, as colleague, teacher, mentor and as an esteemed friend," Smith says. "We're especially proud of her. She was very eloquent and warm and witty all at the same time."

Smith recalls a mid-afternoon break at the Writers Institute offices at SUNYA. "We were talking intensely about literature and race and the phrase came up, 'Could have danced all night,'

BRUCE BOUCHARD, artistic director at Capital Repertory Theatre who worked with Morrison as a producer of "Dreaming Emmett," a drama about Emmett Till that premiered played at Cap Rep in 1986.

"She's a brilliant, tough, uncompromising artist of the first stripe," Bouchard says. "It was a shock for her to come from the solo business of writing novels to be thrown suddenly into this enormously collaborative art form."

Bouchard says there was sometimes tension during rehearsals. "I won't deny there were challenges that came up because it was a play about racial strife and it brought up some incendiary stuff," Bouchard says. "Ultimately, the play made a difference in the world of people who saw it."

It also brought Cap Rep national recognition for the first time, as critics from Time magazine and other national publications came to Albany to see Morrison's first foray into theater. "From our point of view, Toni Morrison landed us in the national spotlight and we were honored to have her," Bouchard says.

Two years after the play, Bouchard and Morrison met unexpectedly in Cafe Cappriccio restaurant. "She saw me, held out her arms and we both just burst out laughing," Bouchard recalls. "We jumped into each other's arms and clapped each other on the back. Dare I say, it was a wonderful release for both of us."

MAUREEN McCOY, novelist and former Schweitzer Fellow, now an assistant professor at Cornell University. Morrison was her mentor and editor at UAlbany.

"I feel exhilarated and blessed to have had her wisdom and keen eye on my work," says McCoy, who acknowledges Morrison's guidance on McCoy's last novel, Divining Blood. "She was very much an adviser to me and was very easy to talk to about the process of writing and has a deep vision for literature."

McCoy recalls shopping with Morrison locally for Morrison's first computer. The computer salesman, who had no idea who Morrison was, inquired, "Are you planning to write a book on this?" Morrison remained poker-faced.

Says McCoy, "I just wanted to shriek out who this was and what she'd be writing on it (the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Beloved). But Toni never let on."

McCoy recalls tromping across Washington Park with Morrison to a workshop for fiction writers in Morrison's apartment nearby. "One of Toni's characters in Beloved follows the blossoms to travel north, and we were feeling giddy, laughing and traipsing through Washington Park, when she pointed to the blossoms on a tree and noted this is how we would mark our progress before streets came in."

McCoy recalls many dinners at Qualters Pine Hills Restaurant with Morrison. "She could talk very seriously about literary ideas or with high humor."

Toni Morrison on "The Book Show"

Interviewed by Tom Smith, Director of the NYS Writers Institute

October 13, 1988

TOM SMITH: My special guest today is novelist Toni Morrison, prize-winning author of Beloved and Song of Solomon and other remarkable novels. Toni, welcome. I can't say welcome to Albany because you're currently Schweitzer Professor of Humanities at the University of [sic] Albany. But it's great to have you on the Public Radio Book Show.

TONI MORRISON: Thank you.

TOM SMITH: And congratulations one more time on Beloved winning this year's, or the 1987, Pulitzer Prize for fiction. And I believe it's now out in Plume paperback?...

TONI MORRISON: Exactly. This month, as a matter of fact.

TOM SMITH: ...in bookstores all over the country. Toni, Beloved is a haunted as well as a haunting story. What was the real historical incident that haunted you into writing the terrible though beautiful tragedy of Sethe and Denver and Baby Suggs and Paul D. and Beloved herself?

TONI MORRISON: It was the story of a woman named Margaret Garner who had run away with her children from, I think, Boone County in Kentucky, into Cincinatti, Ohio, and shortly after she arrived was caught by her owner and chose to--I think what she had in mind was to kill herself and her children rather than be taken back to that plantation, to that farm. She did this in 1850, and the Fugitive Slave Law was very much on everybody's mind, because it granted slave owners the right to go into free territory--

TOM SMITH: Which would have been Ohio.

TONI MORRISON: Ohio...

TOM SMITH: Yes.

TONI MORRISON: ...a non-slave state, and if they found those people, to take them back. It had another kind of edge to it, which was that any free black person walking up and down the street in a free state could be kidnapped and could be identified, mis-identified, or just stolen and called a runaway slave. So that nobody really in a free state was sla...safe, because there was no way in which anybody would pay any attention to what the slave himself or herself said. So it was...there was enormous danger. And the Union, you know, was wracked over that problem, and there was an interesting compromise that involved territory and Melville...Herman Melville's father-in-law, as it turned out, was the one who made it law. So anyway, when this woman and her family arrived at her mother-in-law's place in Cincinatti and she saw them coming for her, she ran out into the backyard and hit her sons in the head with a shovel to kill them and cut the throat of her daughter, and she had a very small child also, and she was about to bash its brains out on the wall when somebody stopped her. The interesting thing about that story, one of the interesting things, is... there were many incidents of infanticide among slave women and mothers for all sorts of reasons. But this woman was interviewed a number of times and everybody remarked on the fact that she was not crazy, she was not frothing at the mouth, she seemed very serene. And the efforts of the abolitionists, black and white, to have her tried for murder, which for them would have been a triumph because to try her for the murder of her daughter would have meant that she was a person, she had some responsibility toward her children, had some claim or legal things to say about her children--they were unsuccessful. And she was tried for what was perceived to be the superior and more outrageous crime, which was the theft of herself, having stolen herself as property, having run away. In real life, of course, she lost that battle and was returned.

TOM SMITH: Yeah.

TONI MORRISON: But the moment...for me the moment of the claims of motherhood, of personhood, what does it mean to have a child and have no rights over its destiny, to be prevented from assuming responsibility, not just love but just responsibility, about how and if it lives. So the trauma for me in a way was...it was a distillation of all of the horrors of slavery in very very personal terms, because as we were saying earlier, slavery...I mean this is 300 years, you know, what part of it, it's too long, too big, too much. So if you try to focus on one human incident with just a few people, it seemed to me it was much more accessible to a modern reader, than not, than trying to do a large quote slavery unquote book. Also nowadays we know more.

TOM SMITH: Yes.

TONI MORRISON: I mean, I think a book like Beloved, written in the 80s, would have a readership unlike any one it would have had in the 30s, or before World War I. Now we know about all sorts of things. We know the consequences of state racism on a personal level.

TOM SMITH: Yes.

TONI MORRISON: We know about child abuse, we know about sexual abuse, we know about...we know about Freud, I mean, you know, psychoanalysis, a lot of information that we...that the reader brings...

TOM SMITH: Yeah.

TONI MORRISON: ...and makes it all...

TOM SMITH: But the...the...the very complicated and traumatic psychology of a mother killing a baby daughter out of an act of love, because that baby daughter is, as she says, the most beautiful...

TONI MORRISON: Yes.

TOM SMITH: ...untouched, pure part of herself...

TONI MORRISON: That's right.

TOM SMITH: ...and her past. I mean, that's mind-boggling but it's a kind of tragic recognition...

TONI MORRISON: Yes.

TOM SMITH: ...well, that all kinds of people are obviously making when they are reading the book...

TONI MORRISON: When they read the book, yes.

TOM SMITH: Yes. And, to go...pick up on something you just said about the enormity, not only the epic length of the whole...slavery and the fallout into abiding racism, but the enormity and the depth of the leg...of that particular legacy of evil. You dedicate your book to the 60 million and more.

TONI MORRISON: Yes.

TOM SMITH: And...as if this particular act of blood-guilt, of remorse, is the way into all those annals. Of course, the character Beloved herself, I mean the young girl who is, or may be, the ghost of Sethe's...

TONI MORRISON: Dead child.

TOM SMITH: ...dead child, she has an inner life, a very interesting inner life, that seems to have...I guess the only way you could call it, race memory of the passage...

TONI MORRISON: Yeah.

TONI MORRISON: ...from Africa, that Sethe's baby in real life could not have had.

TONI MORRISON: Oh yes, she emerged initially as simply what Sethe wanted her to be, the return and forgiveness and...and opportunity to explain. Everyone in the house almost summons her up, even Baby Suggs, the grandmother, Denver, Sethe's daughter, they all seem to need her...the presence of the ghost before Beloved appears on the...in the territory. When she arrives, I had originally believed that she would function that way as a presence that they would assume would be the ghost of the ba...of the daughter at the proper age. And I got very much stuck, because there was something even more hidden equally as memorable, in the history of these black people, that was unarticulated in the legend and in the lore and in the songs, that just didn't exist. And that was the Middle Passage, the actual coming over.

TOM SMITH: Yes.

TONI MORRISON: So I did develop her, as indeed a real person, who as a child had been brought over and who was traumatized by that experience, and who had been locked up, which is, you know, the license of people who bought these girls or boys was complete. And her efforts to remember that experience in a way that was palatable to her, and her identification of Sethe as the Mother, the Other, the face on the ship, that looked as though it were going to smile at her but then chose to throw itself into the sea rather than...you know, all of these rejection...

TOM SMITH: Yes.

TONI MORRISON: ...phenomena, as well as the trauma of being stolen, and being locked up for all those years, makes her language the exact language it would be had she indeed been a real living ghost, whatever that experience is, so when they say, "What was it like over there?", whereas they mean death, the grave, she means the Middle Passage. Names, all of these things, all the...it's...it was the same, it was the...it was a death.

TOM SMITH: Yes. Well, those 60 million and more are, indeed, are the ones who never even made it...

TONI MORRISON: That's right. That's it. Exactly. Yeah. Yeah. I...

TOM SMITH: ...to the New World. It doesn't include at all the horrible beneficiaries of every sense of slavery...

TONI MORRISON: No.

TOM SMITH: ... and racism.

TONI MORRISON: Interesting, those who--of the figures I had gotten, that was the most modest, which is why I put in more. You re...I remember travelogues, travel stories in which people would say that the river, the Congo, which is a very big river, was...they couldn't navigate it because it's...it was choked with bodies.

TOM SMITH: With bodies.

TONI MORRISON: That's a big river...

TOM SMITH: Ohh...yes.

TONI MORRISON: ...that's like the Hudson being choked with bodies, you can't navigate that.

TOM SMITH: I mean that's truly Dantesque...

TONI MORRISON: Of course it is...

TOM SMITH: I mean the rivers of hell...

TONI MORRISON: Exactly.

TOM SMITH: ...embodied in, you know, real geography...

TONI MORRISON: Exactly.

TOM SMITH: ...and history. Well, the multiple lyric voices which you render not only Beloved's long deep interior race memory, but also the other characters who look upon her as the expected one...

TONI MORRISON: Yes.

TOM SMITH: ...the part of their memory that they have lost, including Paul D. as well as Sethe and Denver. And it's almost as if Beloved, the character, the young girl, has this total desire to be subsumed into the mother, that she wants to become part of Sethe again, I mean this is return to the womb with the most mythic vengeance that I've ever encountered.

TONI MORRISON: Oh yes.

TOM SMITH: It makes Freud look so penny-ante...Toni, in Beloved you depict love as being a dangerous emotion for slaves, particularly for mothers. Paul D., I believe, reflects on that, that Sethe had loved too much for a black woman, for a slave, and while he...and he says you gotta love maybe just a little bit, so that when it's lost--and it will always would be...

TM & TS (unison): ...you have some left over.

TOM SMITH: How does...how did that work, and how does that work? I mean, the continuing recognition of that sense of loss and that sense of really total love, is something, I think, fascinating in the book. I mean, it was a historical phenomena [sic], that it was dangerous to love.

TONI MORRISON: Oh, indeed, you're being...the nature...one of the salient points about the nature of being owned is not having the freedom to choose, first of all, whom to love. And also not being permitted to imagine a future, imagine the next day for the beloved, whether it is Baby Suggs' husband, when they just decided well, whichever one gets a chance to go, then go, and we may not have time to say goodbye. Or as she says, "I didn't have a chance to say goodbye to my children." When they were gone, some didn't even have their adult teeth, some didn't have hair under their arms. So as she had children--and they were all required to reproduce, I mean this is a commodity that reproduces itself--she at some point said, "I would not love, and could not love, this one". You conserve the energy if you know you're not going to see their hands change into the hands of an adult, if you know that anyone has a say-so. To spendthrift your emotions would make you incapable to function for the children that you have. So they ration out these emotions, ration them out. For a man like Paul D., who would be a kind of a soldier, fugitive, prisoner, traveler, and having that experience in a...in a prison, where the business of love or even memory, remembering something lovely, can destroy you, because you're not strong enough, affectless enough, tough enough to get through the next day, so you make it small. So if you ever have use for it, you...you...you husband it some. Sethe refused. That was the danger. And the consequences of loving her children the way in which we would assume any parent would...that's all she did, was say "These children are mine." The consequences of that under those circumstances were indeed dangerous, because she would have to follow through. So what does one do if you know that the lives of your children are going to be at least as unliveable, and at least as brutal, as one's own?

TOM SMITH: That's a very moving passage where she reflects of [sic] what's not going to happen...

TONI MORRISON: ...that's right...

TOM SMITH: ...to her daughter

TONI MORRISON: ...not...

TOM SMITH: ...if she kills her.

TONI MORRISON: To me, yes, but not...

TOM SMITH: That...terrible but also stirring.

TONI MORRISON: Right.

TOM SMITH: Now after your four previous novels, which more or less take place in the contemporary world, but they have all particular and memorable visions of black memory. I'm thinking of Pilate in

TONI MORRISON: Oh yes.

TOM SMITH: ...Song of Solomon, I'm thinking of Son in Tar Baby, and so on and so forth. Why did you go back in history? What summoned you to the Civil War era?

TONI MORRISON: I was amazed, really, that I got that compelled about that story, because I really resisted it a lot for all the reasons we suggested. It meant keeping that company in that situation for too many years, that I, you know, thought would be not just difficult but impossible for me. But the past for black people in this country and black people before they came to this country, for novelistic reasons seems to me to be almost infinite. The contemporary world is interesting. The speculation as some writers do on the future is also interesting, but it seems to me that uncharted terrain, unfathomed depths, are yet to be plumbed in the material that's yet to be written about.

TOM SMITH: Which is both historial as well as mythic.

TONI MORRISON: That's right. It has all of the elements of...which make material for novels. The history, the people, the un... the dis- and unremembered. I've been overwhelmed since I began writing that book about one small thing, which is nowhere in this land is there one statue, one wall, to commemmorate a slave who did not make it. Not one.

TOM SMITH: Hence the sixty million...

TONI MORRISON: Hence the sixty million and more.

TOM SMITH: ...and more. That's...that's really remarkable. Now the Civil War...we were talking about not civil, but the institution of slavery and its fallout into continuing racism. We've talked about it as a legacy of evil, a kind of almost a force of blood-guilt, like original sin in American culture and certainly in your work. And memory in that sense is like a fang in the heart. You can see that in Beloved, all the characters, not just Sethe but Baby Suggs the mother-in-law, Denver, the younger...the daughter, the...and Paul D., they struggle to remember but are horrible...horrified at what they remember, and you represent that so magnificently to the reader that you can't wait to turn the page, but the images of half-remembered atrocities, you know, are like nothing else. You know, there's a question that seems to be implicit in your work, and it really isn't...not only in Beloved but I think in some ways in Tar Baby and Song of Solomon. How much should we remember and tell? How much do we owe the burden of the past?

TONI MORRISON: We have to remember all of it. The problem is remembering it in a coherent, productive fashion. Which is why art is important. It's one of the ways in which we can remember without it being disorderly, carcinogenic, destructive memory.

TOM SMITH: Yes.

TONI MORRISON: You know, if it's disorderly, if it's chaotic, you don't know...it'll hurt. It'll destroy. Which is why those people didn't remember. They had to move on.

TOM SMITH: There's something about total recall, both...you know, as an emotional force as well...not just a literal experience...

TONI MORRISON: Yes.

TOM SMITH: ...that is not only overwhelming, it's crazy-making...

TONI MORRISON: That's true.

TOM SMITH: ...in some way, it is not really the transformation of the past into meaning.

TONI MORRISON: No.

TOM SMITH: I think...

TONI MORRISON: It's just data...

TOM SMITH: ...it's the ending of Beloved.

TONI MORRISON: ...under those circumstances, yeah.

TOM SMITH: And really the end of Milkman, Dead's pilgrimage in Song of Solomon, strikes me the same way. Is there a special--well, let me put it to you this way. We all have a burden of the past, our individual and collective. But do you think there's a special story that black women know, a very special transmission of the truth? And I'm ovbiously alluding to some of your characters, I mean, not only Sethe and Baby Suggs and Pilot, so on and so forth. I mean, Pilot who listens to the ghost of her father, whose bones are sometimes mistaken for coal she carries [bound? unclear] for. What a fantasic and appropriate metaphor that is.

TONI MORRISON: In an interesting way they bear, carry the culture, in a way in which its intimacy and its personal, private relationship with the past, with the dead--women after all shroud the dead, and they bury the dead--makes it...stands...puts it apart, in some way, from the recollection that perhaps we have been accustomed to by men. But what interests me about the position of women in black literature and in the history is not only that they were sort of dismissed and silenced for such a long long time, and also the perception that the freedom story is a male story, of running away or getting caught, there were all these men who were trying to get their families. The facts don't support that. There were women with whole wagonloads of children because the men were picked off so easily and so quickly. Also, the women had this network among themselves, as women frequently do, where they could trade, exchange, the gossip, the information, the lore, the medicine, they were the agencies frequently for life. There were no other agencies for feeding one another, for helping one another. And also they took upon themselves these extraordinary things, when you think about it. The major people who were ferrying slaves out of slavery into free land were women. Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, these were girls who themselves were functioning as pilots and spies and were making these contacts to literally take, you know, set up the situation and help slaves who didn't know where they were going. I mean, they didn't know--if they couldn't read signs, there were no signs--and take them into free territory.

TOM SMITH: So that they were both actors and also the great repositories...

TONI MORRISON: That's right.

TOM SMITH: ...of this epic passage.

TONI MORRISON: Exactly. I call them...they become both the ship and the safe harbor.

TOM SMITH: Yes. Oh, that's wonderful. How about your own family lore? Because, Toni, on the one hand you're this acclaimed and sophisticated international novelist. On the other hand, in reading not just Beloved but Song of Solomon, Sula, The Bluest Eye--you also, and this is particularly true, I think, in Song of Solomon and Beloved--you seem to be also a transmitter of folktales, of legends, and I just wonder how that came to you, how you melded together [inaudible]...

TONI MORRISON: Well, it began as a..I think the way it does in most families in...of whatever ethnic origin. But for black people, storytelling was critical, partly because of the heritage of the griot and the heritage of memorizing and the geneaologies that are in fact in song, the song of the family that is in Song of Solomon is based on the song that is indeed in my family.

TOM SMITH: Is that right?

TONI MORRISON: Yeah, which my mother and aunts know, and I have heard. I don't remember it all but it...in it is a rhyming scheme which is about a great-grandfather and his sons, and so on. Very circum [inaudible] ical...

TOM SMITH: [Nice? unclear]...metaphor of flight takes so many aspects in your book.

TONI MORRISON: But those stories were very much a part of growing up. And at first, when I first began to write, I just thought it was parochial, it's my family, and maybe some of the things from the neighborhood. And learned as a young adult that they were simply repeating to me stories that a lot of black people, if not all black people, had heard in some form or another.

TOM SMITH: Toni, in the time left, I'd like to ask you about the ambiguities of freedom, that heavy word, freedom, in your work. Contrast...for example, Milkman's quest for identity is also a search for love and courage. And it seems when he becomes connected, when he finds commitment and family, then he is most free. On the other hand, Jadine, the tar baby of your novel Tar Baby, goes for independence in the modern, you know, colloquial sense, finds it in the sophistication of the white world. She seems to be not free. How does that work? I mean, that...

TONI MORRISON: Well, there...it's such a big word, it seemed to me important in these novels to sort of slice it down. There's freedom, there's license, there's self-indulgence, there's self-regard. Freedom, I think I'm trying to say, is when one is able to choose one's responsibilities, not to not have responsibilties but to have the right and the ability to make those choices, and then to make them. Milkman is able to do...make a commitment, and risk something at the same time. Be willling to give it up. So that death has no claim. You know, once you're terrified of losing your things, losing your stuff, and dying, that's a kind of prison. That's what Jadine has. She doesn't want to lose her status, her glamour, her geographical mobility, her social mobility. That is her notion of freedom. But if you're not willing to lose it, give it up, then it's already a pair of manacles on you. And on the other hand, you have Son, who has none of these things holding him down, none at all. He is really formally free, but has a fraudulent nostalgia for [Elow?] and the South that will not stand up to a very modern tar baby like Jadine.

TOM SMITH: So both of them, antithetical lovers...

TONI MORRISON: That's right.

TOM SMITH: ... as they are, are incomplete...

TONI MORRISON: Incomplete, incomplete.

TOM SMITH: ...you see, both Son and Jadine. One question about Guitar, the blood brother...

TONI MORRISON: Yes.

TOM SMITH: ...of Milkman in Song of [Solomon]... His racial consciousness starts off with having humane values very much like Pilot's, and yet leads to violence and hatred. Is there a particular hazard in that kind of...

TONI MORRISON: There's a hazard if your solutions are murder. I mean, we know that there are holy wars, and we know, you know, decided which ones were good and which ones were not. But if the solutions are death, then you can end up where death is a solution to everything.

TOM SMITH: Thank you very much Toni, we have run out of time, remarkably. We'll look forward to the next episode of Beloved, which I think is coming in the future from you, and thanks so much for being with us on the Public Radio Book Show.